Modular Arithmetic

Concepts and Definitions

Modular arithmetic : is a system of arithmetic for integers, which considers the remainder.

Modulo and Modulus : It is basically an operator which is denoted by mod and in programming uses % symbol.

\(a \mod N, \ \ a \rightarrow dividend, N \rightarrow divisor \ (Modulus \ | \ Moduli)\)

identity element / neutral element : The element of a set of numbers that when combined with another number under a particular binary operation leaves the second number unchanged

\(a + 0 = a\)

\(a \times 1 = a\)

inverse element : is another element in the set that, when combined on the right or the left through the binary operation, always gives the identity element as the result.

\(a + b = 0 \rightarrow 5 + (-5) = 0\)

\(a \times b = 1 \rightarrow 5 \times ({1 \over 5}) = 1\)

The integers modulo p define a field, denoted by

\(F_{p} = \left\{ 0,1,...,p-1 \right\}\)

under both addition and multiplication there is an inverse element b for every element a in the set, such that a + b = 0 and a * b = 1.

If the modulus is not prime, the set of integers modulo n define a ring. \(F_{n}\)

Congruence

Definition by Remainder after Division

\(\text{Congruence modulo } m \text{ is defined as the relation } \equiv \ (mod\ m) \text{ on the set of all } a,b \in \mathbb{Z}\)

\(a \equiv b \ (mod\ m) \ \Longleftrightarrow \ a \mod m = b \mod m\)

Definition by Integer Multiple

\(\text{We also see that } a \text{ is congruent to } b \text{ modulo } m \text{ if their difference is a multiple of } m\)

\(a \equiv b \ (mod\ m) \ \Longleftrightarrow \ \exists k \in \mathbb{Z} \ \ : \ \ a - b = km\)

EX

And

GCD from Congruence Modulo m

\(\text{Let } a,b, \text{ and } m \in \mathbb{Z}\)

\(a \equiv b \ (mod\ m) \ \Longrightarrow \ \gcd(a, m) = \gcd(b, m)\)

\(\text{Since } a \equiv b \ (mod\ m) \ \Longrightarrow \ \exists k \in \mathbb{Z} \ \ : \ \ a = b + km\) \(\ \Longrightarrow \ a + km \equiv b \ (mod\ m) \\)

\(\text{Let } N = a \times b \ \text{ and } \ \exists k \in \mathbb{Z}\)

\(a + kN \equiv a \ (mod\ ab) \ \Longrightarrow \ a + kN \equiv a \ (mod\ N) \ \Longrightarrow \ c \equiv a \ (mod\ N)\)

\(\text{Since } a \text{ is a factor of } N \text{ then } \ \Longrightarrow \ \gcd(c, N) = a\)

Modular arithmetic properties

-

\((a+b) \mod n = [(a \mod n) + (b \mod n)] \mod n;\)

-

\((a-b) \mod n = [(a \mod n) - (b \mod n)] \mod n;\)

-

\((a\times b) \mod n = [(a \mod n)\times (b \mod n)] \mod n;\)

-

\(10^a \mod n = (10 \mod n)^a;\)

My property ^^

- \(k^{e} \times (x^{e_{1}}y^{e_{2}}z^{e_{3}})^{e_{4}} \equiv k \times (xyz)^e \equiv xyz \equiv 0 \ (mod\ xyz);\)

Properties of addition

-

\(\text{If} \ a + b = c, \ then \ a \ (mod\ N) + b \ (mod\ N) \equiv c \ (mod\ N);\)

-

\(\text{If} \ a \equiv b \ (mod\ N), \ then \ a + k \equiv b + k \ (mod\ N); \ \text{for any integer} \ k\)

-

\(\text{If} \ a \equiv b \ (mod\ N) \ and \ c \equiv d \ (mod\ N), then \ a + c \equiv b + d \ (mod\ N);\)

-

\(\text{If} \ a \equiv b \ (mod\ N), then -a \equiv -b \ (mod\ N);\)

Properties of multiplication

- \(\text{If} \ a \times b = c, then \ a \ (mod\ N) \times b \ (mod\ N) \equiv c \ (mod\ N);\)

EX

since

we have

-

\(\text{If} \ a \equiv b \ (mod\ N), then \ ka \equiv kb \ (mod\ N); \ \text{for any integer} \ k\)

-

\(\text{If} \ a \equiv b \ (mod\ N), and \ c \equiv d \ (mod\ N)\ , then \ \ ac \equiv bd \ (mod\ N);\)

Properties of Exponentiation

- \(\text{If} \ a \equiv b \ (mod\ N), then \ a^{k} \equiv b^{k} \ (mod\ N); \ \text{for any positive integer} \ k\)

EX

we observe that

so

The last digit of a number is equivalent to the number taken modulo 10.

Fermat's Little Theorem

knwing that \(p\) is a prime number

-

\(a^{p} \equiv a \ (mod \ p)\)

-

\(a^{p-1} \equiv 1 \ (mod \ p)\)

-

\(a^{-1} \equiv a^{p-2} \ (mod\ p)\)

HOW ?

Euler's Phi-Function | Euler's totient Function

-

\(\varphi(1) = 0;\)

-

\(\varphi(p) = p-1;\ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ p \ is \ prime\)

-

\(\varphi(m \times n) = \varphi(m) \times \varphi(n); \ \ \ \ \ \ m \ and \ n \ are \ coprimes\)

-

\(\varphi(p^e) = p^e - p^{e-1};\ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ p \ is \ prime\)

Euler's Theorem

-

\(a^{\varphi(n)} \equiv 1 \ (mod \ n)\)

-

\(a^{k \times \varphi(n) + 1} \equiv a \ (mod \ n)\)

-

\(a^{-1} \equiv a^{\varphi(n) - 1} \ (mod\ n)\)

Modular Inverse

\(\text{A modular inverse of an integer} \ b \ (mod\ n) \ \text{is the integer} \ b^{-1} \text{ such that :}\)

- \(b \times b^{-1} \equiv 1 \ (mod\ n)\)

\(\text{So for any element} \ g \ \text{in the field} \ F_{p} \ (not \ F_{n}) \ \text{there exists a unique integer } d \ \text{in the field such that}\)

- \(g \times d \equiv 1 \ (mod\ p) \ \ \ \ OR \ \ \ \ g \times d \ mod \ p = 1\)

EX1

From the third Fermat's Little Theorem

hence

finally

EX2

Notice that n = 10, which is not a prime number

But since g and n are relatively prime, we will apply the third Euler's Theorem

hence

finally

from Crypto.Util.number import inverse

inverse(3, 13)

#====================================================

def egcd(a, b):

if a == 0:

return b, 0, 1

else:

gcd, u, v = egcd(b % a, a)

return gcd, v - (b // a) * u, u

def modinv(a, n):

gcd, x, y = egcd(a, n)

if gcd != 1:

return None # modular inverse does not exist

else:

return x % n

modinv(3, 13)

Quadratic Residue

If q and n are coprime integers, then q is called a quadratic residue modulo n if the following congruence has a solution

- \(x^{2} \equiv q \ (mod\ n), \ where \ x \in F_{n}\)

Likewise, if it has no solution, then it is called a quadratic non-residue modulo n.

So the square root of the Quadratic Residue modulo an integer equal ±x

And the square root of the None Quadratic Residue modulo an integer does not exist !!

if n is a prime number you will find out that exactly half of the integers between 1 and p−1 are squares mod p, that is, the congruence

- \(x^{2} \equiv q \ (mod\ p), \ where \ x \in F_{p}\)

has a \(\frac{p-1}{2}\) solutions

EX

Find ALL quadratic residues mod 5

So the quadratic residues mod 5 are 1,4 and the non-residues are 2,3

A number that is congruent to 0 mod p is neither a residue nor a non-residue.

Euler's criterion

A number x is square root of q under modulo p if

\(x^{2} \equiv q \ (mod\ p)\)

Properties of quadratic (non-)residues

-

\(\text{Quadratic Residue} \times \text{Quadratic Residue} = Quadratic Residue\)

-

\(\text{Quadratic Residue} \times \text{Quadratic Non-Residue = Quadratic Non-Residue}\)

-

\(\text{Quadratic Non-Residue} \times \text{Quadratic Non-Residue = Quadratic Residue}\)

an easy way to remember this :

\(\text{Quadratic Residue} \leftarrow 1, \ \ \ \text{Quadratic Non-Residue} \leftarrow 0\)

Legendre symbol

The Legendre Symbol gives an efficient way to determine whether an integer is a quadratic residue modulo an odd prime p

\(\frac{q}{p} \equiv q^{(\frac{p-1}{2})} \ (mod\ p)\)

Legendre's Symbol obeys:

\(\left\{\frac{q}{p} = 1\right\} \ \text{if} \ q \ \text{is a quadratic residue and} \ q \not\equiv 0 \ (mod\ p)\)

\(\left\{\frac{q}{p} = -1\right\} \ \text{if} \ q \ \text{is a quadratic non-residue mod p}\)

\(\left\{\frac{q}{p} = 0\right\} \ \text{if} \ q \equiv 0 \ (mod\ p)\)

Which means given any integer a, calculating pow(q, (p-1)//2, p) is enough to determine if q is a quadratic residue.

Tonelli-Shanks algorithm

is a technique for solving for x in a congruence of the form:

\(x^{2} \equiv q \ (mod\ p)\)

which is also the square root of quadratic residue modulo a prime

sage: from sage.rings.finite_rings.integer_mod import square_root_mod_prime

sage: q = ... # the Quadratic Residue

sage: p = ... # the modulus

sage: q = Mod(q, p)

sage: square_root_mod_prime(q, p)

Tonelli-Shanks doesn’t work for composite (non-prime) moduli,

The main use-case for this algorithm is finding elliptic curve co-ordinates

Chinese Remainder Theorem (CRT)

gives a unique solution to a set of linear congruences if their moduli are coprime.

\(x \equiv a_{1} \mod n_{1}\)

\(x \equiv a_{2} \mod n_{2}\)

\(. \ . \ .\)

\(x \equiv a_{k} \mod n_{k}\)

There is a unique solution :

\(x \equiv a \mod N, \ where \ N = n_{1} \times n_{2} \times ... \times n_{k}\)

EX

Given the following set of linear congruences:

Find the integer a such that

the Solution

sage: CRT_list([2,3,5], [5,11,17])

872

Modular Binomials

Binomials Theorem

\(\text{According to the theorem, it is possible to expand any nonnegative integer power of } (x + y) \text{ into a sum of the form }\)

\((x + y)^{n} = \sum_{k=0}^{n} \binom{n}{k} x^{n-k} y^{k} = \sum_{k=0}^{n} \binom{n}{k} x^{k} y^{n-k}\)

\(\text{Knowing that } \binom{n}{k} = \frac{n!}{k! \ (n-k)!}\)

\((x+y)^n = \binom{n}{0} x^n y^0 + \binom{n}{1} x^{n-1} y^1 + \binom{n}{2} x^{n-2} y^2 + \cdots + \binom{n}{n-1} x^1 y^{n-1} + \binom{n}{n} x^0 y^n\)

So

\(\ (x+y)^n \equiv (x)^{n} + (y)^{n} \ (mod\ m)\)

EX

Rise both sides of first equation to e2 and the second one to e1

Multiply both sides of first equation with 2^(-1 * e1 * e2) and the second one with 5^(-1 * e1 * e2)

Subtract both equations from each other

we can get the value of the left hand side since all values are known (lets call it X)

Diffie-Hellman (DH - Exponential Key Exchange Method)

\(\text{Every element of a finite field } F_{p} \text{ can be used to make a subgroup } H \text{ under repeated action of multiplication.}\)

\(\text{In other words, for an element } g : H = \{g, g^{2}, g^{3}, ...\}\)

Primitive Elements / Generators

\(\text{A primitive element of } F_{p} \text{ is an element whose subgroup } H = F_{p}\)

\(\text{which means that every element of } F_{p} \text{ can be written as } \rightarrow \ g^{n} \ mod\ p\) \(, \ n \in \mathbb{Z}\)

\(\text{Because of this, primitive elements are sometimes called generators of the finite field}\)

There could be more than one primitive element for the finite field, and rather than using a set and checking if every element of Fp has been

generated, we can also rapidly disregard a number from being a generator

by checking if the cycle it generates is smaller in size than p.

If we detect a cycle before p elements, g can't be a generator of Fp.

def is_generator(g, p):

for n in range(2, p):

if pow(g, n, p) == g:

return False

return True

p = 28151

for g in range(p):

if is_generator(g, p):

print(g)

sage: GF(28151).primitive_element()

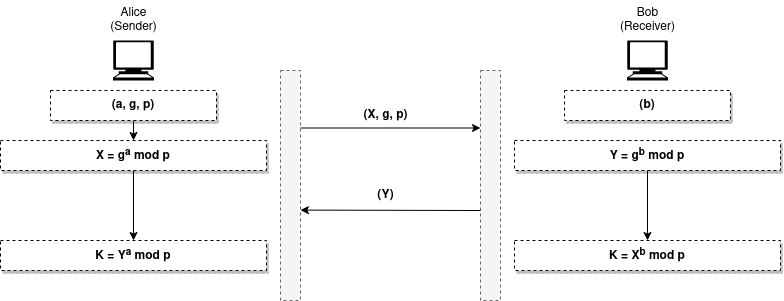

DH Protocol/Procedure

-

Establish a prime number

pand some generator of the finite fieldg -

The user then picks a secret integer

a(Private Key) , wherea < p, then calculates

\(X = g^{a} \ mod\ p\)

-

The user will send

g,p(Public Key) andX, making it so difficult to calculatea(by taking the discrete logarithm). -

The receiver then picks a secret integer

b(Private Key) , whereb < p, then calculates

\(Y = g^{b} \ mod\ p\)

-

Then he will send back

Y -

Now both sides can generate their shared keys as follows

\(K \ = \ X^{b} \ mod\ p \ = \ Y^{a} \ mod\ p \ = \ g^{a \times b} \ mod\ p\)

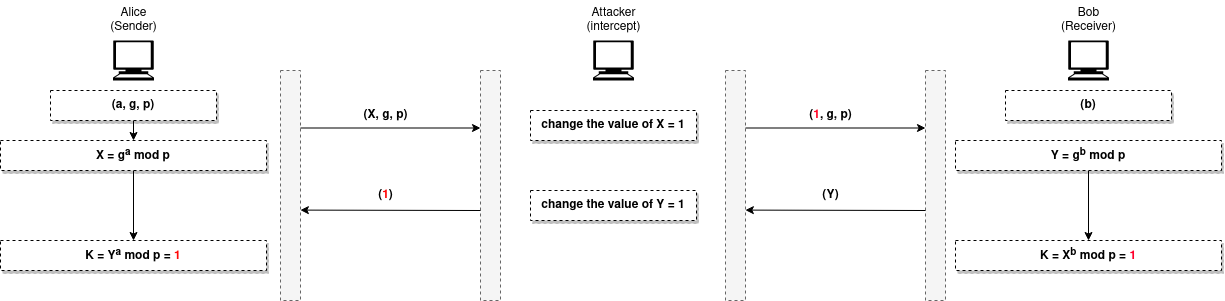

MITA

Discrete Log Problem (DLP)

we mentioned that using the primitive element g, every element in Fp can be written as :

\(X = g^{n} \ mod\ p\)

knowing only the values of X, g, and p leaving as with the problem of finding n, and this is known as the discrete log problem.

\(n = log_{g}(X) \ mod\ p\)

The discrete logarithm problem is considered to be computationally intractable. That is, no efficient classical algorithm is known for computing discrete logarithms in general.

\(\text{all known algorithms run in } O(2^{N^{C}}) \text{ , where } C > 0\)

from sympy.ntheory import discrete_log

# A = g^a mod p

a = discrete_log(p, A, g)

# A = g^a mod p

# using Pohlig-Hellman and baby-step giant-step alogrithms

sage: a = discrete_log(A, Mod(g, p))

# OR using a Pari znlog (linear sieve index calculus method)

sage: int(pari(f"znlog({int(A)},Mod({int(g)},{int(p)}))")) # a bit faster

sage: gp.znlog(A, gp.Mod(g, p))

# using sagemath

def pohligHellmanPGH(p,A,g):

#g must be small

F=IntegerModRing(p)

g=F(g)

A=F(A)

G=[]

H=[]

X=[]

c=[]

N=factor(p-1)

for i in range(0,len(N)):

G.append(g^((p-1)/(N[i][0]^N[i][1])))

H.append(A^((p-1)/(N[i][0]^N[i][1])))

X.append(log(H[i],G[i]))

c.append((X[i],(N[i][0]^N[i][1])))

print("G=",G,"\n","H=",H,"\n","X=",X)

#Using Chinese Remainder

c.reverse()

for i in range(len(c)):

if len(c) < 2:

break

t1=c.pop()

t2=c.pop()

r=crt(t1[0],t2[0],t1[1],t2[1])

m=t1[1]*t2[1]

c.append((r,m))

print("(a,p-1) =",c[0])

sage: a = pohligHellmanPGH(p, A, g)

sage: a

# G= [8213473543459478292, 3854530033786951538, 15842502293236950997, 11361374755113076881, 4654654383183389733]

# H= [7794196832818169365, 1, 12912327280035100030, 14801588540420624265, 15860493449920325450]

# X= [3, 0, 83, 1881, 73825648379]

# (a,p-1) = (3466191685115160123, 16007670376277647656)

References

- https://g.co/kgs/jsEVup

- https://cryptohack.org/